Fear of Love: Leos Carax's "Annette"

Leos Carax has always inserted himself into his movies one way or another (literally in the case of his two most recent features), using cinema as a means through which to explore his feelings about himself, those he loves, and the world around him. Far from the blending of life and reality of a Hong Sangsoo or Philippe Garrel, however, Carax takes advantage of the tools of the medium and cloaks and codifies his “language” with that of a maximal stylist. The works of Carax plunge into the depths of cinema and its possibilities; he animates and ennobles the medium. In this way he is a rare sort of innovator whose films tend to awaken cinema, to render it anew. His early work is unabashedly romantic, both in relation to the art form and in his depictions of lovesick passion. Holy Motors (2012), his return to feature filmmaking after a 13-year absence, found the director’s romanticism at odds with an increasingly cold, virtual world, and even within this ambivalence found inspired ways of how to engage with it. His latest, Annette, a musical originated by the band Sparks, finds Carax on the far side of that romanticism that once defined him.

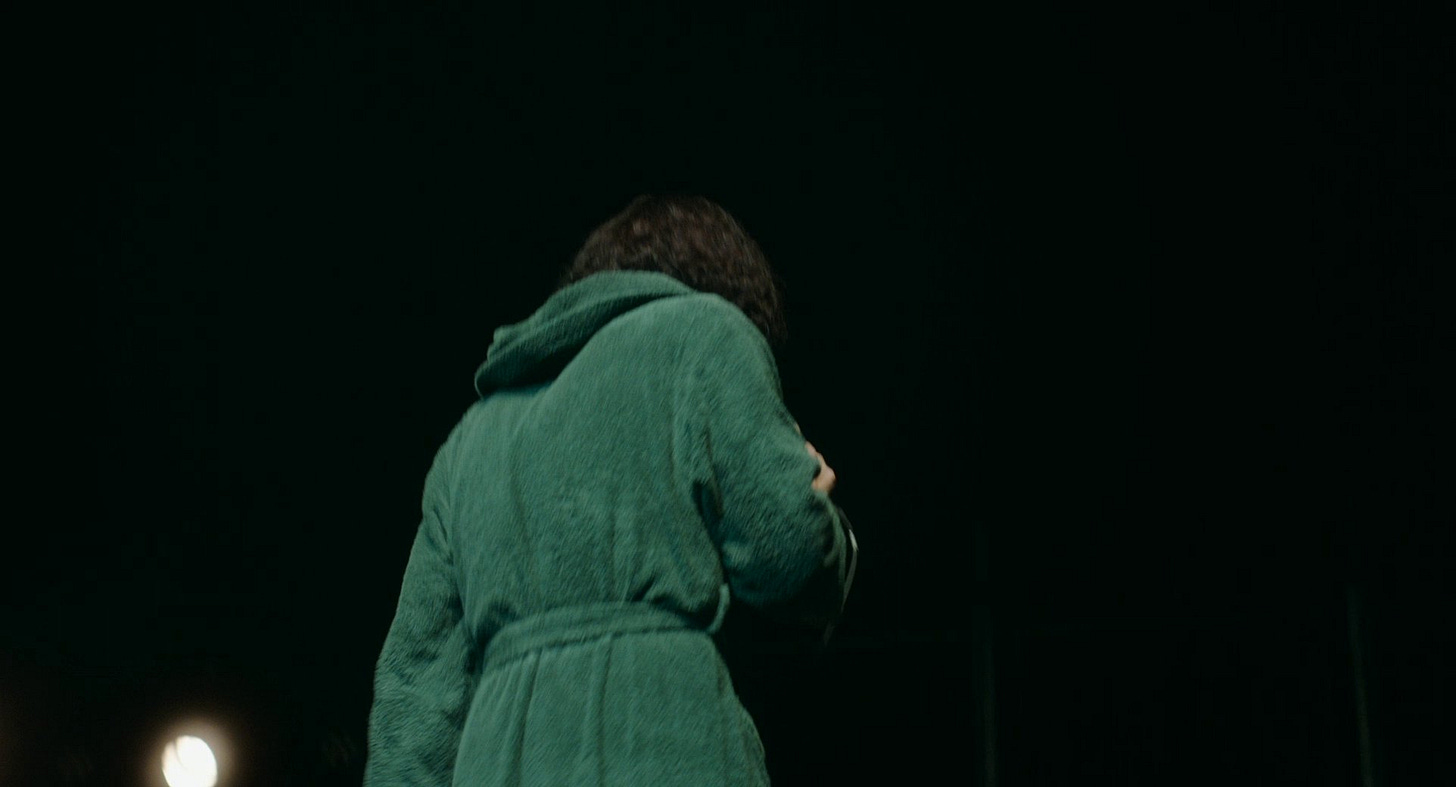

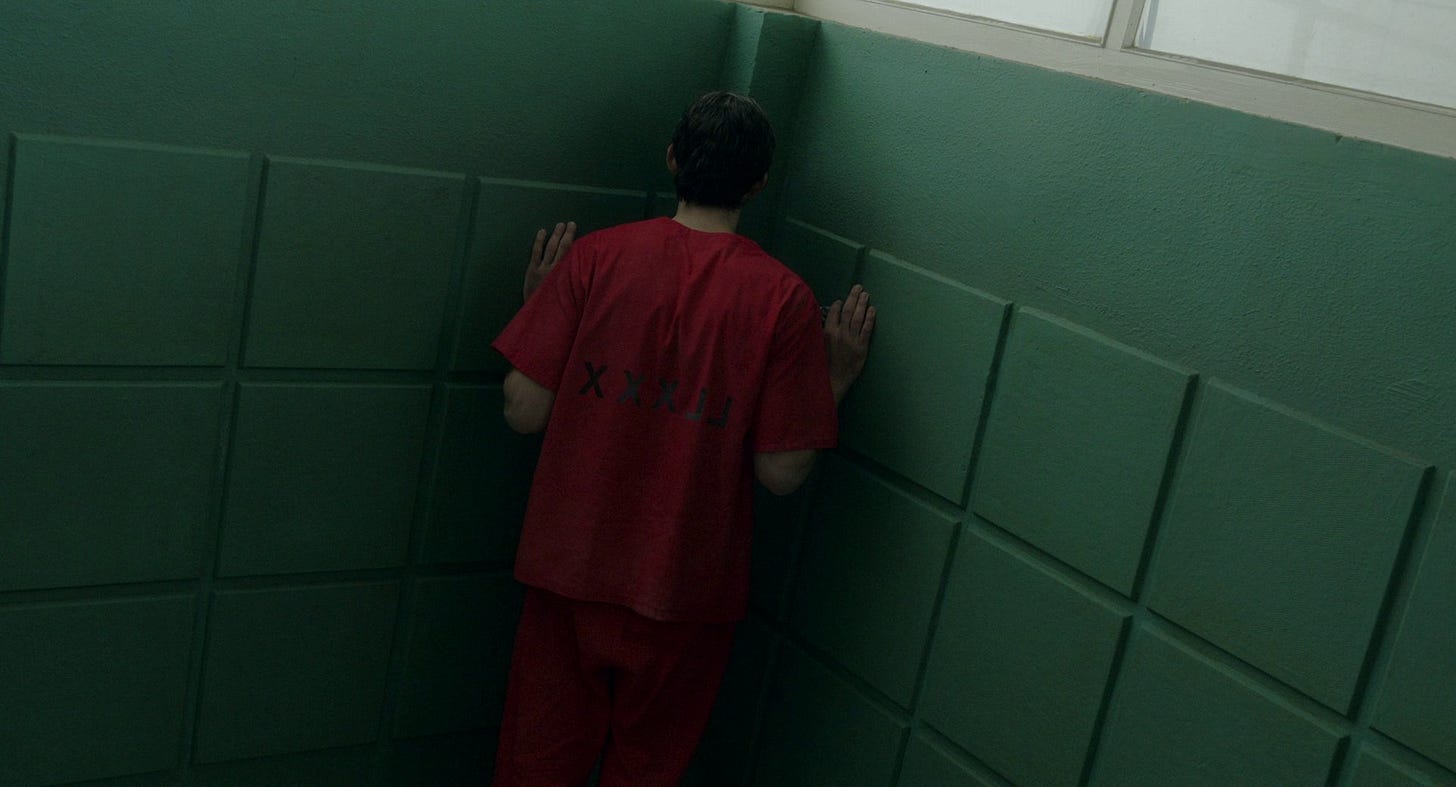

Boy Meets Girl (1984), Mauvais sang (1986), and Les amants du Pont-Neuf (1991) all concern themselves with the emotional rollercoaster at the outset of infatuation. Annette’s starting point is at the beginning of the decline of a relationship. It’s a film intensely imbued with real life regrets, tumult, and reflection. Hints of Carax’s own experiences and emotions abound, as do those of Sparks, who all channel not just later-life considerations of relationships but also their own up and down careers, their relationships to fame, to art, audiences, and to the loved ones whose autonomous inner worlds and respective passions can become obstructions to the ambitions of single-minded artists. Boldly, there’s no initiation for the audience of the romance of Henry (Adam Driver as a bad boy comedian) and Ann (Marion Cotillard as a renowned opera singer). They are engaged to be married and already at the tail end of the honeymoon phase of their relationship. Henry harbours reservations, expressing skepticism about Ann’s vocation (“she dies and dies and dies and bows and bows and bows”) on stage at one of his provocative shows. “Being in love makes me sick” he says, linking him to Denis Lavant’s Carax-avatar from previous films, whose character names Alex (Carax’s real name) and Oscar are the source of the director’s anagrammatic pseudonym. Not unlike De Niro’s Jimmy Doyle in New York, New York, his ego cannot abide the success of his lover. Driver’s Henry, however, is far less likeable or redeemable, his despicable behaviour devolves quickly and exponentially.

Annette tackles narcissism, insecurity, and self hatred, expressing anxieties around partnerships, creation, success, and fatherhood, as well as the role of art and the artist in our contemporary culture (hence the pointed contrast of Ann’s and Henry’s respective mediums and yet their rhyming lostness on stage). The two poles here are that of the sublime and the abyss, of beauty and of abjection. The former is represented by the highs of artistic creation and the birth of the titular child (who takes the form of a marionette!)—the ultimate artistic creation whose purity is a harsh reminder of the ways we fail ourselves and each other. The latter is what swallows Henry and keeps him from meeting the beauty that surrounds his life.

The tongue in cheek humour of Sparks makes for a surprisingly good match for Carax’s own playfulness and they align perfectly in their mutual sincerity. It might be easy for some viewers to mistake their style(s) for pure irony and the off-putting appearance of the Baby Annette marionette could be a deal killer. The wavelength here is far more direct and emotional than it may come off in the sarcastic contemporary landscape. The literal simplicity of the Sparks brothers’s lyrics bring Annette closer to the realm of opera than of the Hollywood musical, and their marvellous compositions are often deeply rousing. Songs like “We Love Each Other So Much” feature the same lines repeated over and over and are more interested in how to build emotions through melody and rhythmic structure, not unlike "My Baby's Taking Me Home" off of the Sparks’ album Lil' Beethoven. Clearly for Carax, the brothers’s project and initial direction proved inspiring, having led to a collaboration seven years in the making, resulting in a formal triumph. The precise use of colour, geometrical design, and the sense of movement feels closer to the whimsy of Carax’s early films even as Annette treads in more sober, reflexive territory. There has always been a musicality to his style, memorable sequences like the “Modern Love” scene in Mauvais sang and the fireworks medley spectacle of Lovers on a Bridge aside, all of his images are constructed and fit together with synaesthesic ecstacy.

The eventual arrival of the marionette disrupts and alters the film, just as it does to the lives of the characters. The choice to use a marionette to play Baby Annette, Carax’s own, is a brilliant one. The artificiality emphasizes her uniqueness of being: she is something to behold, to treasure, to be worthy of (and thus in Henry’s case is the final trigger before he gives into the abyss altogether). Bewildered and perhaps even blind to the beauty she represents, Henry stares at her, holds her away from himself, observing her as if to try and figure out just what she is, what she means. Ann dances with her, in touch with Annette’s profundity. She is magic, a miracle. When Henry discovers that Annette has an inexplicable ability to sing like her mother, he turns her into a money-making sensation, taking the sublime into the realm of abjection, into the abyss.

The dramatic arc of the film also works in the hyperbolic register of opera. While I doubt (and hope) such overt betrayal (and death) figures in the pasts of Annette’s creators, one can infer allusions to Carax’s relationship with Juliette Binoche at a time where they were both exciting stars in the film scene but her stock was rising on a much larger scale. In a self-implicating gesture, Driver seems to be made up to look more and more like Carax when he gets his comeuppance in the film’s final scenes. The film also takes a deconstructive approach to its own form, bringing the musical into unusual territory. In one shot, Driver and Cotillard make love while singing and in another he goes down on her. At one point Cotillard sits on a toilet and smokes a cigarette amidst a solo. All of these examples and others are all the more impressive considering they were recorded live on set as opposed to the more typical lip-synching approach. You can hear Cotillard strain when she has to sing while swimming in backstroke.

Sparks and Carax gleefully subvert while also never losing sight of the emotional seriousness at the core. For all of Annette’s dark views on life, love, and art, it also is the work of creators in love with creating. The film’s formal makeup and spirit embodies the very duality it explores of the sublime and of the abyss. Carax laments the romance of his past while also trying to move towards it. If Holy Motors was a frightened view of a new, colder, virtual world, then Annette is more keen on confronting how one might live within it and pointing to what matters. Baby Annette becomes a metaphor for what we may risk losing in our culture. Art which uses the unreal, reaches for the sublime, in the face of a world of abjection. Henry’s choices are all the more tragic for this reason: he isn’t just a failed partner, father, and artist, but represents a movement away from the broader hope that lies behind love, family, and art.

In Carax’s view of the 21st century, we’re so far gone that the ideal role of the artist has all but dissolved. Everything is commodified, corrupt, globalized. Whatever connections to the sacred that existed are severed. It’s what Holy Motors faced and it’s what Annette has come to terms with. So what is Carax’s answer? It’s simple: to love your children. Carax and his daughter Nastya are in the film’s opening scene. She was also in Holy Motors. The film is dedicated to her. Henry is torn apart by a broken culture and his own weakness. He betrays his greatest creation. Annette beckons for the opposite. You take care of who is right next to you. That’s your world. As the film gets bleaker and bleaker, the beauty of Baby Annette herself shines through more and more—the scene in which she performs for the first time is one of the most stunning sequences in recent memory and is eventually topped by a climactic duet with Driver—as does the film’s discreet tenderness which permeates every note and every shot. It’s still a tragedy, and a heartbreaking one at that, but the film’s own existence is antidotal to its implications. Carax has made the sort of pop spectacle lacking in our present day. It suggests alternative possibilities for our culture and for cinema. Annette exemplifies Carax’s uncanny ability to make cinema new again, to make it exciting, wondrous, and awe-inspiring. He is a creator of new images and a defier of clichés who reaches for the sublime and transcendent capabilities of the art form—and for the first time in many years is back to having fun doing so.

If you enjoy this and any other pieces, please consider supporting Long Voyage Home by becoming a paid subscriber.

More on Carax: