Pour la beauté du geste: Leos Carax's "Holy Motors"

The following piece was originally published in Paper Issue #1 of La Furia Umana in 2013 and was not previously available online.

Endeavouring to construe an accurate description of just what Holy Motors is can mostly just further confuse those simply asking, “What’s it about?” Answers to that question are more successful when taking the “less is more” approach; it is difficult to top, for instance, the perfectly succinct one-liner currently on Wikipedia: “[Denis] Lavant plays a man who travels between multiple parallel lives.” The ground between bare-bones synopsis and wide range parsing is perhaps not worth exploring for such an aggressively discursive film. It would be easy to mistake Motors’ circumvention of typicality as incoherency, rather, what we have here is the new, and the new is liable to cause one to pause. One of the highest compliments that can be paid to this film is that it does not so simply fit into a comfortable mold. This is virtuoso filmmaking of the highest order. What else could one expect from a too-long cinematically repressed Leos Carax, whose last feature, the misunderstood masterpiece Pola X, was released 13 years ago.

Holy Motors stars the inimitable Denis Lavant, who plays Monsieur Oscar—an ambiguous figure whose absence of definition is key to one of the film’s primary themes: identity. Céline (Edith Scob), a figure just as unclear to us, drives him around Paris in a limousine to various destinations. At each stop, Oscar adorns a new visage, transforming in the back of the limo with an assortment of costumes and makeup. Oscar performs a task under each assumed identity. Why and for whom he is performing these duties is never explained; “solving” this mysterious concept is not in the cards. It is the viewer’s job to look through it to see Carax’s metaphorical (and metaphysical) concerns. Oscar’s shifting identities show us a world shifting from the real to the virtual, wherein the role(s) of the human being, and therefore the artist, are being transformed.

Denis Lavant is credited with no less than eleven roles in the film; they are labeled as follows: Monsieur Oscar; Banker; Beggar woman; Motion capture specialist; Monsieur Merde; The father; The accordionist; The killer; The victim; The dying man; and The man in the house. As his character slips in and out of identities, Lavant brilliantly shifts from one extreme to another, answering whatever call Carax demands. Surely this is the most accomplished of all his performances, and the richest of his collaborations with Carax (each feature aside from Pola X has featured Lavant). From the physical contortions of a hunchback gypsy to the flips, kicks, and rhythmic gyrations of a motion capture artist to the stern reprimand dished out by a disappointed father, Lavant demonstrates his range and capability as a performer that have earned him comparisons to Chaplin, Chaney and Michel Simon. What anchors his performance, despite his mutability, is a constant melancholy employed here with great emphasis. Lavant’s suggestive stare acts as both a window and barrier to a mysterious and complex soul. This is a repeated, anchoring motif; it punctuates those lonely, cold moments in the back of the limo when Monsieur Oscar quietly prepares for his next appointment.

Lavant’s status as a descendant of acting legends synchs with Carax’s cineaste persona, bound up as it is with the history of movies. Like each of his other films, Holy Motors integrates Carax’s reverence for cinema’s past into the language of his mise en scène. The first image of the film is one of the earliest that exists, from one of Etienne-Jules Marey’s locomotion studies of the late 1800s. This dream-echo of cinema’s beginning wakes Carax, who appears as himself. His first reaction is to reach for a cigarette (he is rarely seen without one in real life). He then wanders from his dark room into an adjacent cinema, populated with an audience either sleeping or dead. The pure image of cinema’s origins resurrects Carax, who promptly discovers that the union of spectator and film is threatened. In spite of his strange new surroundings he begins anew and next we meet Monsieur Oscar. This is not a film that can be reduced to “dream logic”, this is the waking up from a dream, the facing of a digital reality in which identity is molded more than it is defined.

We never meet the real Monsieur Oscar, we see him awake at the beginning of the film and then go to sleep as somebody else at the end. Carax has likened Oscar to The Tramp in Chaplin’s Modern Times but he is caught “in the threads of an invisible web” as opposed to being “caught up in the cogs of a machine”. This is a helpful point of comparison. Chaplin expressed the anxieties facing the individual by an increasingly industrial world; here Carax expresses the anxieties facing the individual in the Internet age, as the physicality of machines gives way to the material vacancy brought on by computer technology. Exactly what is the real “self” takes on a new set of ambiguities in the 21st century. And then there’s cinema, which has always been linked to materiality and is losing its physical dignity. In one scene, perhaps the only transparent one in the film, Oscar is greeted in the limousine by “The man with the birthmark” (Michel Piccoli), and the dialogue makes Carax’s feelings explicit: “I miss the cameras. They used to be heavier than us. Then they became smaller than our heads. Now you can’t see them at all.” But Holy Motors is affirmative in spite of these pessimistic musings. More than a film of disillusionment, it is a film of curiosity. In this respect it is comparable to Martin Scorsese’s Hugo. The resemblance only goes so far, but both Motors and Hugo are made by artists who revere film history and integrate it into new forms, though one is optimistic—Scorsese—more than skeptical. Both find new forms of cinematic expression without detaching from the lineage they place themselves in, and Carax’s inquisitiveness overwhelms his dismay.

Holy Motors interacts with Carax’s own filmography as well. In the sequence where Oscar becomes a motion capture artist, he is asked to board a treadmill. Carax frames him from the side in front of a green-screen displaying various colorful graphics. It is a sequel to one of Carax’s most memorable shots, that of Lavant (“Alex”) running down an endless street to David Bowie’s “Modern Love” in Mauvais sang (1986). This time, however, the whimsical cinematic spirit of the earlier tracking shot is replaced with a slow push-in, conveying the illusion of tracking from the scrolling phantasmagoria in the background. Now the ground moves for Lavant (Alex? Oscar?) and instead of him spontaneously erupting into an ecstatic expression of his love (and Carax’s love for cinema), he is being coldly commanded by a disembodied voice to perform until he can eventually stand it no longer.

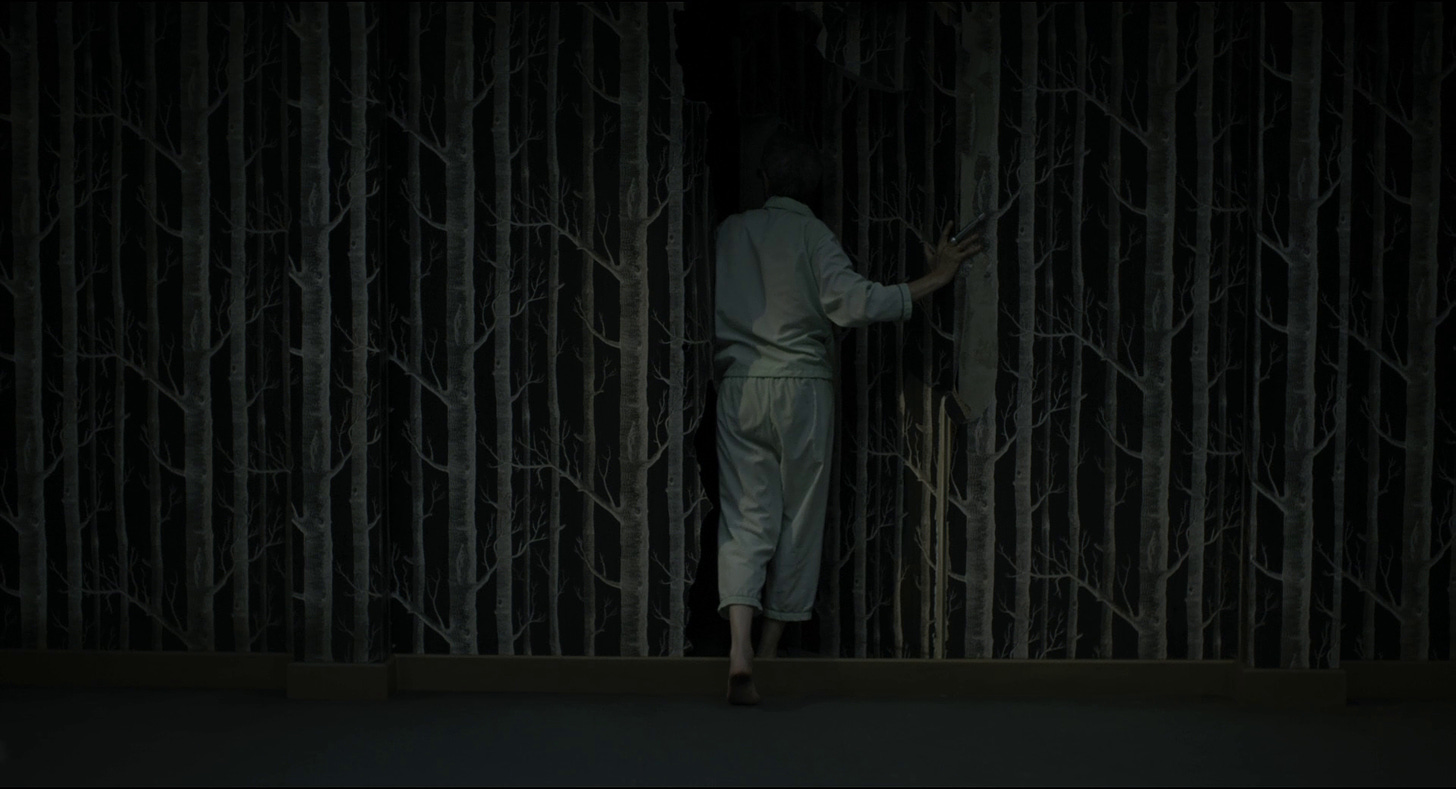

The individual is oppressed, but who or what is the oppressor? In one scene, as the limousine drives through a cemetery, the frame suddenly becomes data-moshed without explanation, without narrative logic. Reality—in Carax’s terms, the medium of film itself—is challenged. The digital world Carax presents in Holy Motors is one in which a certain perception of reality ceases. Memories of celluloid haunt this Paris of pixels. Donning a mask like her character in Eyes Without a Face, the Georges Franju classic, Edith Scob represents just one of the ghosts of cinema’s past. In light of that allusion and the wandering enigma that is M. Oscar, one could re-title Motors “Souls Without a Place”.

Carax is a director concerned with sensuality as much as with ideas, who can grow restless and burst into an expression of emotion without concern for narrative construction. There is just too much love left intact in the filmmaking for this to solely be lament. Back in that scene in the limo, Piccoli’s character asks: “what makes you carry on, Oscar?”, to which a barely veiled Carax replies: “What made me start: the beauty of the act”. In Holy Motors—a film of pleasure, fear and hope—it is with another act of beauty that Carax continues.

If you enjoy this and other pieces, please consider supporting Long Voyage Home by becoming a paid subscriber.