Imaging: Rear Window Ethics

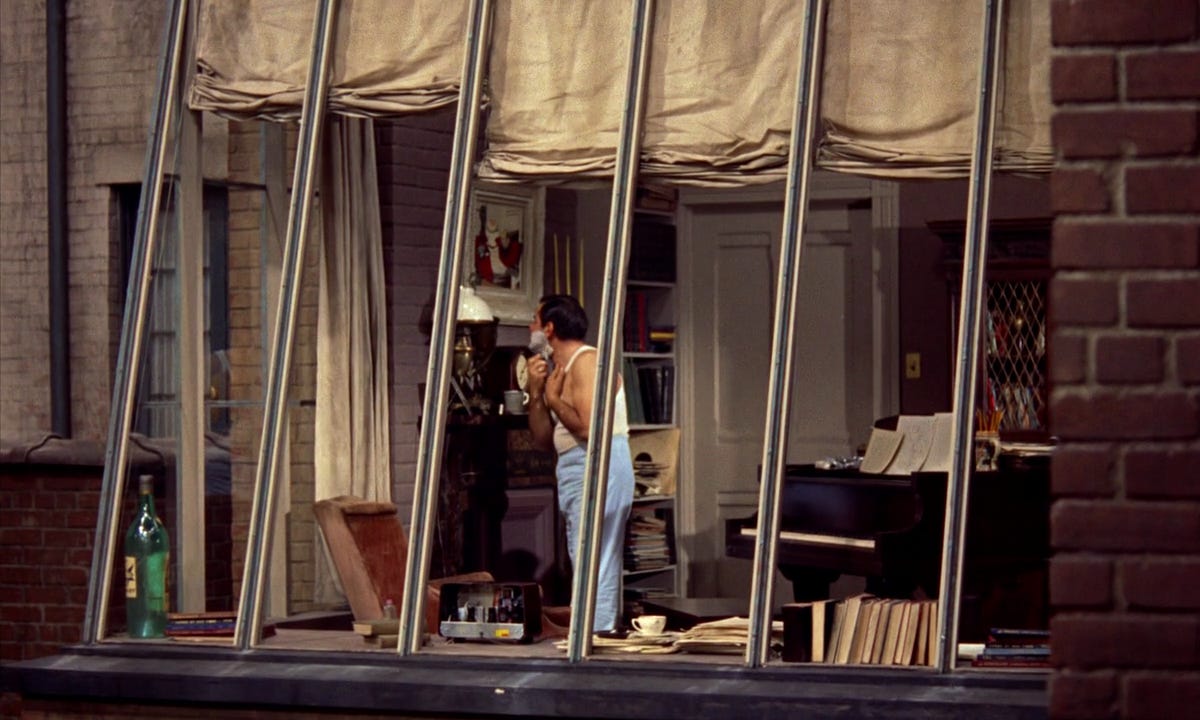

For the first two thirds of Rear Window (1954), Alfred Hitchcock commits to a strict set of rules in regards to his film’s presentation of its infamous setting, roughly limited to an approximation of the range of perspectives available to its wheelchair-bound protagonist, L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart), as he observes activity in the buildings opposite and adjacent to his apartment and in the courtyard that lies in between. Excepting objective views of Jefferies (limited to shots just outside or within the apartment) and pointed departures from his subjectivity that (very) occasionally show us things he does not see or shots that give us a closer, more privileged view of what he is looking at, Hitchcock presents the cast of characters and the glimpsed goings-on of their private lives as though there is an uncrossable axis as defined by the purview of the titular rear window.

The framing and viewing through various windows figured as boxes and rectangles within the memorable set and the meticulous staging therein has invited obvious connections between the voyeurism within the diegesis of Rear Window and the voyeurism inherent to spectatorship. Indeed, Hitchcock is interested in the underlying perversity in the act of watching movies—this fact informs the formal choices of many of his films—but Rear Window’s treatment of the voyeuristic gaze is hardly limited to spectatorship in this sense. Spectatorship here characterizes our very experience of the world. It sets the boundaries for what we can and cannot experience for ourselves. The film mounts a subtly tragic articulation of a modern condition that relates the limits of living versus the intrigue of looking to our relationship with our neighbours, and, more broadly speaking, others.

Two thirds into the film, Hitchcock subverts these rules. The central romance involving Jeffries and Grace Kelly’s Lisa has to this point been stalled by our protagonist’s wandering gaze. Just when they have finally shuttered the windows and refocused their attention on what is right under their nose, a scream gives out.

The neighbours’ dog is discovered dead, with its neck broken, lying in the middle of the courtyard for all to see. A ruckus ensues and various neighbours rush to their windows and balconies, perhaps out of concern or perhaps driven by the very same sort of voyeuristic curiosity that has led Jefferies to the unfolding murder mystery that is the film’s MacGuffin.

The axis is crossed: we see characters from different vantage points for the first time.

Briefly, the fragmented neighbours are united in wide shot, connected by a passive empathy that teases human connectivity and yet ultimately further pronounces their divisions.

Another angled view is introduced, suggesting the crisscrossing gazes of others.

Between sobs, the heartbroken dog owner curses her neighbours for the death of her beloved pet:

“Which one of you did it?! Which one of you killed my dog?! You don’t know the meaning of the word ‘neighbours’! Neighbours like each other, speak to each other, care if anybody lives or dies. But none of you do! But I couldn’t imagine any of you being so low that you’d kill a little, helpless, friendly dog. The only thing in this whole neighbourhood who liked anybody! Did you kill him because he liked you?!”

We see her palpable sorrow resonate with “Miss Torso” and the vulnerable “Miss Lonely Hearts” as well as our principal couple. Such a cry for help contains the longing to not be contained to the self, to share one’s suffering. But human suffering is not enough to make us one. Thus, Hitchcock breaks through his imposed axis to express the transient shared experience of the tragic death of a dog only to further point to and illustrate the alienating borders between individual lives that, whether transparent like windows or opaque like walls, cannot be crossed.

Once the commotion has passed, the rules are back into effect.

Imaging is an ongoing series.